Special Note to the Interventionist Neocon Warmonger Mark Levin -

War and Foreign Policy, By Murray N. Rothbard

This essay is a chapter from Murray Rothbard’s For A New Liberty.

“Isolationism,” Left and Right

“Isolationism” was coined as a smear term to apply to opponents of American entry into World War II. Since the word was often applied through guilt-by-association to mean pro-Nazi, “isolationist” took on a “right wing” as well as a generally negative flavor. If not actively pro-Nazi, “isolationists” were at the very least narrow-minded ignoramuses ignorant of the world around them, in contrast to the sophisticated, worldly, caring “internationalists” who favored American crusading around the globe. In the last decade, of course, antiwar forces have been considered “leftists,” and interventionists from Lyndon Johnson to Jimmy Carter and their followers have constantly tried to pin the “isolationist” or at least “neoisolationist” label on today’s left wing.

Left or right? During World War I, opponents of the war were bitterly attacked, just as now, as “leftists,” even though they included in their ranks libertarians and advocates of laissez-faire capitalism. In fact, the major center of opposition to the American war with Spain and the American war to crush the Philippine rebellion at the turn of the century was laissez-faire liberals, men like the sociologist and economist William Graham Sumner, and the Boston merchant Edward Atkinson, who founded the “Anti-Imperialist League.” Furthermore, Atkinson and Sumner were squarely in the great tradition of the classical English liberals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and in particular such laissez-faire “extremists” as Richard Cobden and John Bright of the “Manchester School.” Cobden and Bright took the lead in vigorously opposing every British war and foreign political intervention of their era and for his pains Cobden was known not as an “isolationist” but as the “International Man.”1 Until the smear campaign of the late 1930s, opponents of war were considered the true “internationalists,” men who opposed the aggrandizement of the nation-state and favored peace, free trade, free migration and peaceful cultural exchanges among peoples of all nations. Foreign intervention is “international” only in the sense that war is international: coercion, whether the threat of force or the outright movement of troops, will always cross frontiers between one nation and another.

“Isolationism” has a right-wing sound; “neutralism” and “peaceful coexistence” sound leftish. But their essence is the same: opposition to war and political intervention between countries. This has been the position of antiwar forces for two centuries, whether they were the classical liberals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the “leftists” of World War I and the Cold War, or the “rightists” of World War II. In very few cases have these anti-interventionists favored literal “isolation”: what they have generally favored is political nonintervention in the affairs of other countries, coupled with economic and cultural internationalism in the sense of peaceful freedom of trade, investment, and interchange between the citizens of all countries. And this is the essence of the libertarian position as well.

(More)

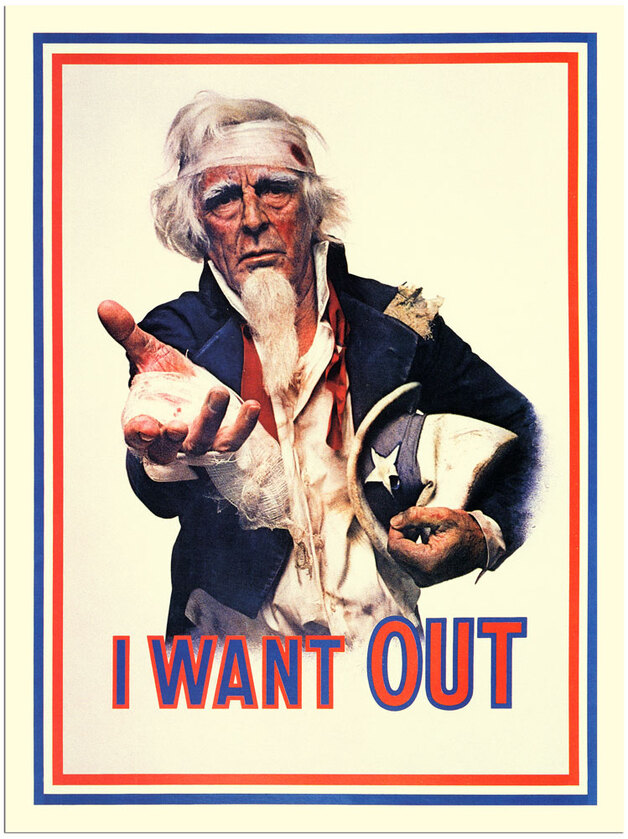

A Foreign Policy Program

To conclude our discussion, the primary plank of a libertarian foreign policy program for America must be to call upon the United States to abandon its policy of global interventionism: to withdraw immediately and completely, militarily and politically, from Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, from everywhere. The cry among American libertarians should be for the United States to withdraw now, in every way that involves the U.S. government. The United States should dismantle its bases, withdraw its troops, stop its incessant political meddling, and abolish the CIA. It should also end all foreign aid – which is simply a device to coerce the American taxpayer into subsidizing American exports and favored foreign States, all in the name of “helping the starving peoples of the world.” In short, the United States government should withdraw totally to within its own boundaries and maintain a policy of strict political “isolation” or neutrality everywhere.

The spirit of this ultra-“isolationist,” libertarian foreign policy was expressed during the 1930s by retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley D. Butler. In the fall of 1936, General Butler proposed a now-forgotten constitutional amendment, an amendment which would delight libertarian hearts if it were once again to be taken seriously. Here is Butler’s proposed constitutional amendment in its entirety:

"The removal of members of the land armed forces from within the continental limits of the United States and the Panama Canal Zone for any cause whatsoever is hereby prohibited.

The vessels of the United States Navy, or of the other branches of the armed service, are hereby prohibited from steaming, for any reason whatsoever except on an errand of mercy, more than five hundred miles from our coast.

Aircraft of the Army, Navy and Marine Corps is hereby prohibited from flying, for any reason whatsoever, more than seven hundred and fifty miles beyond the coast of the United States.20"

Disarmament

Strict isolationism and neutrality, then, is the first plank of a libertarian foreign policy, in addition to recognizing the chief responsibility of the American State for the Cold War and for its entry into all the other conflicts of this century. Given isolation, however, what sort of arms policy should the United States pursue? Many of the original isolationists also advocated a policy of “arming to the teeth”; but such a program, in a nuclear age, continues the grave risk of global holocaust, a mightily armed State, and the enormous waste and distortions that unproductive government spending imposes on the economy.

Even from a purely military point of view, the United States and the Soviet Union have the power to annihilate each other many times over; and the United States could easily preserve all of its nuclear retaliatory power by scrapping every armament except Polaris submarines which are invulnerable and armed with nuclear missiles with multi-targeted warheads. Bur for the libertarian, or indeed for anyone worried about massive nuclear destruction of human life, even disarming down to Polaris submarines is hardly a satisfactory settlement. World peace would continue to rest on a shaky “balance of terror,” a balance that could always be upset by accident or by the actions of madmen in power. No; for anyone to become secure from the nuclear menace it is vital to achieve worldwide nuclear disarmament, a disarmament toward which the SALT agreement of 1972 and the SALT II negotiations are only a very hesitant beginning.

Since it is in the interest of all people, and even of all State rulers, not to be annihilated in a nuclear holocaust, this mutual self-interest provides a firm, rational basis for agreeing upon and carrying out a policy of joint and worldwide “general and complete disarmament” of nuclear and other modern weapons of mass destruction. Such joint disarmament has been feasible ever since the Soviet Union accepted Western proposals to this effect on May 10, 1955 – an acceptance which only gained a total and panicky Western abandonment of their own proposals!21

The American version has long held that while we have wanted disarmament plus inspection, the Soviets persist in wanting only disarmament without inspection. The actual picture is very different: since May 1955, the Soviet Union has favored any and all disarmament and unlimited inspection of whatever has been disarmed; whereas the Americans have advocated unlimited inspection but accompanied by little or no disarmament! This was the burden of President Eisenhower’s spectacular but basically dishonest “open skies” proposal, which replaced the disarmament proposals we quickly withdrew after the Soviet acceptance of May 1955. Even now that open skies have been essentially achieved through American and Russian space satellites, the 1972 controversial SALT agreement involves no actual disarmament, only limitations on further nuclear expansion. Furthermore, since American strategic might throughout the world rests on nuclear and air power, there is good reason to believe in Soviet sincerity in any agreement to liquidate nuclear missiles or offensive bombers.

Not only should there be joint disarmament of nuclear weapons, but also of all weapons capable of being fired massively across national borders; in particular bombers. It is precisely such weapons of mass destruction as the missile and the bomber which can never be pinpoint-targeted to avoid their use against innocent civilians. In addition, the total abandonment of missiles and bombers would enforce upon every government, especially including the American, a policy of isolation and neutrality. Only if governments are deprived of weapons of offensive warfare will they be forced to pursue a policy of isolation and peace. Surely, in view of the black record of all governments, including the American, it would be folly to leave these harbingers of mass murder and destruction in their hands, and to trust them never to employ those monstrous weapons. If it is illegitimate for government ever to employ such weapons, why should they be allowed to remain, fully loaded, in their none-too-clean hands?

The contrast between the conservative and the libertarian positions on war and American foreign policy was starkly expressed in an interchange between William F. Buckley, Jr., and the libertarian Ronald Hamowy in the early days of the contemporary libertarian movement. Scorning the libertarian critique of conservative foreign policy postures, Buckley wrote: “There is room in any society for those whose only concern is for tablet-keeping; but let them realize that it is only because of the conservatives’ disposition to sacrifice in order to withstand the [Soviet] enemy, that they are able to enjoy their monasticism, and pursue their busy little seminars on whether or not to demunicipalize the garbage collectors.” To which Hamowy trenchantly replied:

It might appear ungrateful of me, but I must decline to thank Mr. Buckley for saving my life. It is, further, my belief that if his viewpoint prevails and that if he persists in his unsolicited aid the result will almost certainly be my death (and that of tens of millions of others) in nuclear war or my imminent imprisonment as an “un-American”….

I hold strongly to my personal liberty and it is precisely because of this that I insist that no one has the right to force his decisions on another. Mr. Buckley chooses to be dead rather than Red. So do I. But I insist that all men be allowed to make that decision for themselves. A nuclear holocaust will make it for them.22

To which we might add that anyone who wishes is entitled to make the personal decision of “better dead than Red” or “give me liberty or give me death.” What he is not entitled to do is to make these decisions for others, as the prowar policy of conservatism would do. What conservatives are really saying is: “Better them dead than Red,” and “give me liberty or give them death” – which are the battle cries not of noble heroes but of mass murderers.

In one sense alone is Mr. Buckley correct: in the nuclear age it is more important to worry about war and foreign policy than about demunicipalizing garbage disposal, as important as the latter may be. But if we do so, we come ineluctably to the reverse of the Buckleyite conclusion. We come to the view that since modern air and missile weapons cannot be pinpoint-targeted to avoid harming civilians, their very existence must be condemned. And nuclear and air disarmament becomes a great and overriding good to be pursued for its own sake, more avidly even than the demunicipalization of garbage.

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2000/04/murray-n-rothbard/subverting-peace-and-freedom-2/